BRIAN Woollard was clearing out his father’s old shed when he found a box full of war memorabilia.

He took and kept a little notebook. But it wasn’t for another two decades that he looked inside it and discovered the detailed diary his father had kept while he was serving in the First World War.

Brian, of Kilmaine Road, Dovercourt, said: “I was doing a six-year apprenticeship in carpentry and couldn’t do my national service until I was 21.

“I was in Malaya - a few of my friends in Singapore were having a drink. I was woken in the middle of the night and was told I must fly back to England as my father was dangerously ill.

“He had a perforated ulcer and was in hospital. He died, it was 1962.

“At my parents home in Queen’s Road, Burnham, I was clearing out his shed - as kids we weren’t allowed in there.

“I found this deed box on the top shelf, I’d never seen it before.

“There were medals and things as well in there - I never knew anything about that whatsoever.

“I don’t know what happened to the rest of it but I kept a notebook, I didn’t know what it was.”

Despite working in the civil service and moving around a lot, Brian kept the notebook for more than 20 years before opening it.

The 80-year-old added: “In about 1986 I sat down and read this.

“I had no knowledge of what he had been through at all, I was the youngest of five and none of my sisters had known about it at all either.

“He had beautiful handwriting and a fantastic memory.”

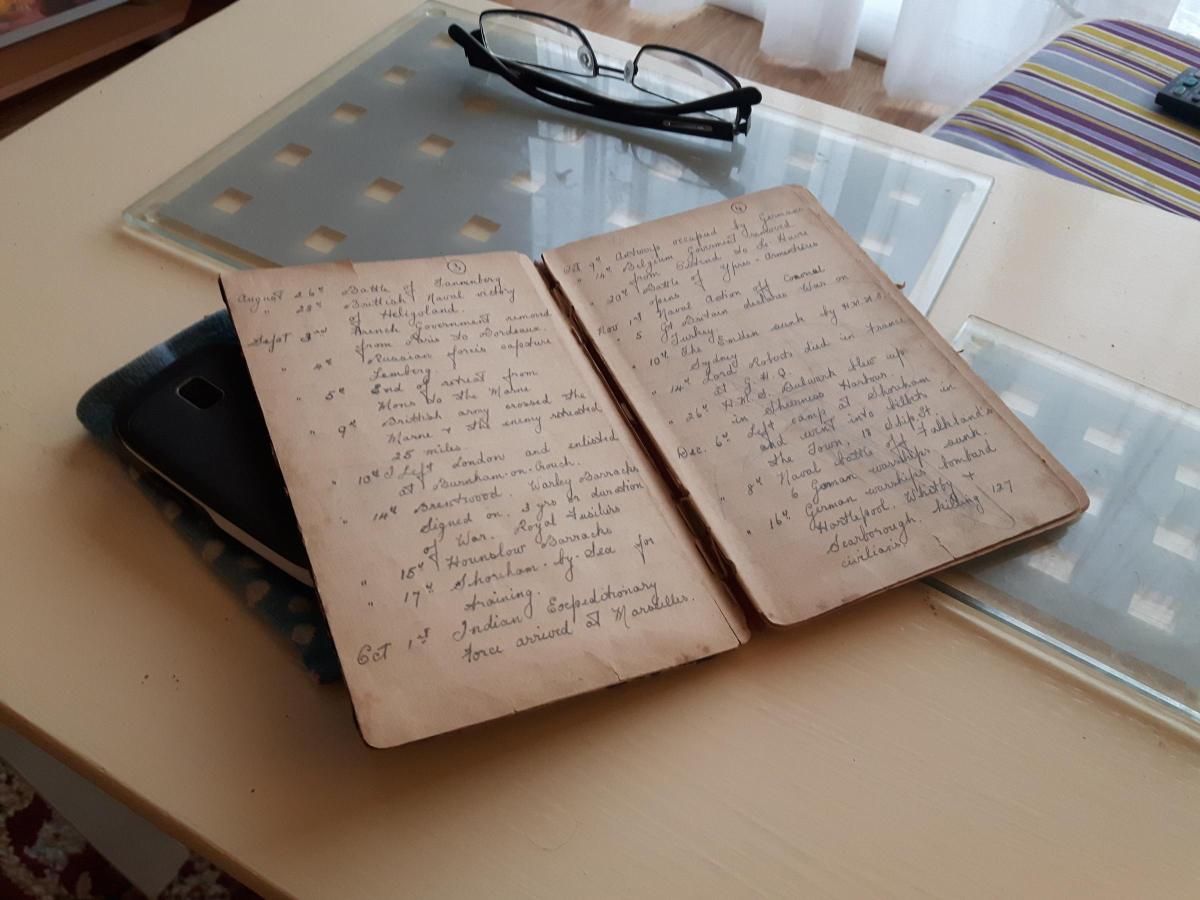

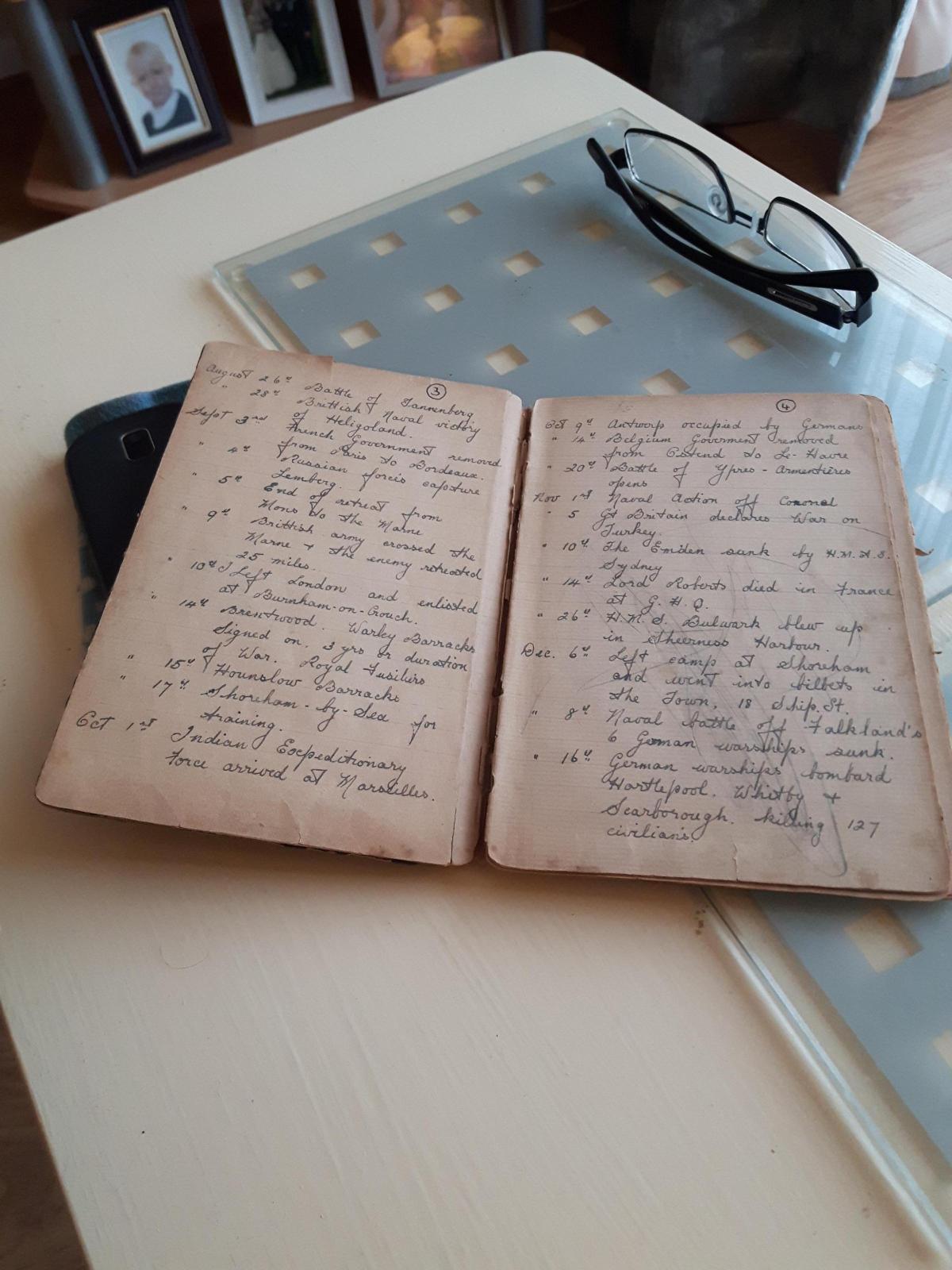

Because the diary is in such good condition, Brian thinks his father, Bertie William Woollard, must have written in the notebook after the war using notes he had taken while serving.

Brian added: “He must have made notes, his handwriting is amazing.

“How could he have kept it in his pocket during the Somme?”

Sergeant Woollard, a painter and decorator by trade, served with the Royal Fusiliers.

His diary starts on June 28, 1914, saying “Archduke Ferdinand and his wife assassinated at Sarajevo” and follows with the dates when war was declared by Austria on Serbia, Germany declaring war on Russia and Great Britain declaring war on Germany.

Dates of events are listed until September 10 when the entry says he left London and enlisted at Burnham-on-Crouch, aged 19.

He said: “Brentwood, Warley Barracks, signed on, three years or duration of war. Royal Fusiliers.”

On September 17, he reports being in Shoreham-by-Sea for training and later a course of firing on Bisley Rifle Range where he said he “finished a first class shot”.

Details of general war news are mixed in with his own agenda, including one entry on December 25, 1914.

It says: “First aeroplane raid on England. Dinner and concert at St Mary’s Hall, Shoreham by Sea.”

On August 28, 1915, he wrote that he was placed on orders for active service.

He travelled to Boulogne in France and was billeted in an “old cow shed with part of a roof and no door.”

On September 25 he wrote: “Battle of Loos commenced. Our battalion left en-route for the firing line, we arrived in the front-line trenches, which were knee-deep in mud and water.

“We were in this battle for four days without food or water and were then relieved by the Guards after having 481 of our men killed and wounded.”

The Battle of Loos was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units.

British casualties at Loos were about twice as high as German losses.

Bertie went on to fight in Ypres, in the trenches at Hooge, carried bombs to the front line at the Battle of the Somme, and in the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Then in January 1917 he was sent to train with nine other men from his company for a raid on the German front-line at the Battle of the Loos.

He said: “We raided the German front line, going over the top at 6.45am. As the ground was covered with snow, we were wearing while smocks and white helmets, so as we could not be seen so well by the enemy.

“We brought back 24 German prisoners with us, and we had four men killed and a few wounded.”

Apart from a sprained ankle and a slight wound to one leg, causing short hospital stays, Sgt Woollard escaped injury, even when he went “over the top at Ypres” and had all his men killed and wounded.

He went home to Burnham and carried on working as a painter and decorator until he had a bad fall in his later years. He died aged 67.

Copies of his war diary have been given to the Imperial War Museum as well as museums in Burnham and Dunkirk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel